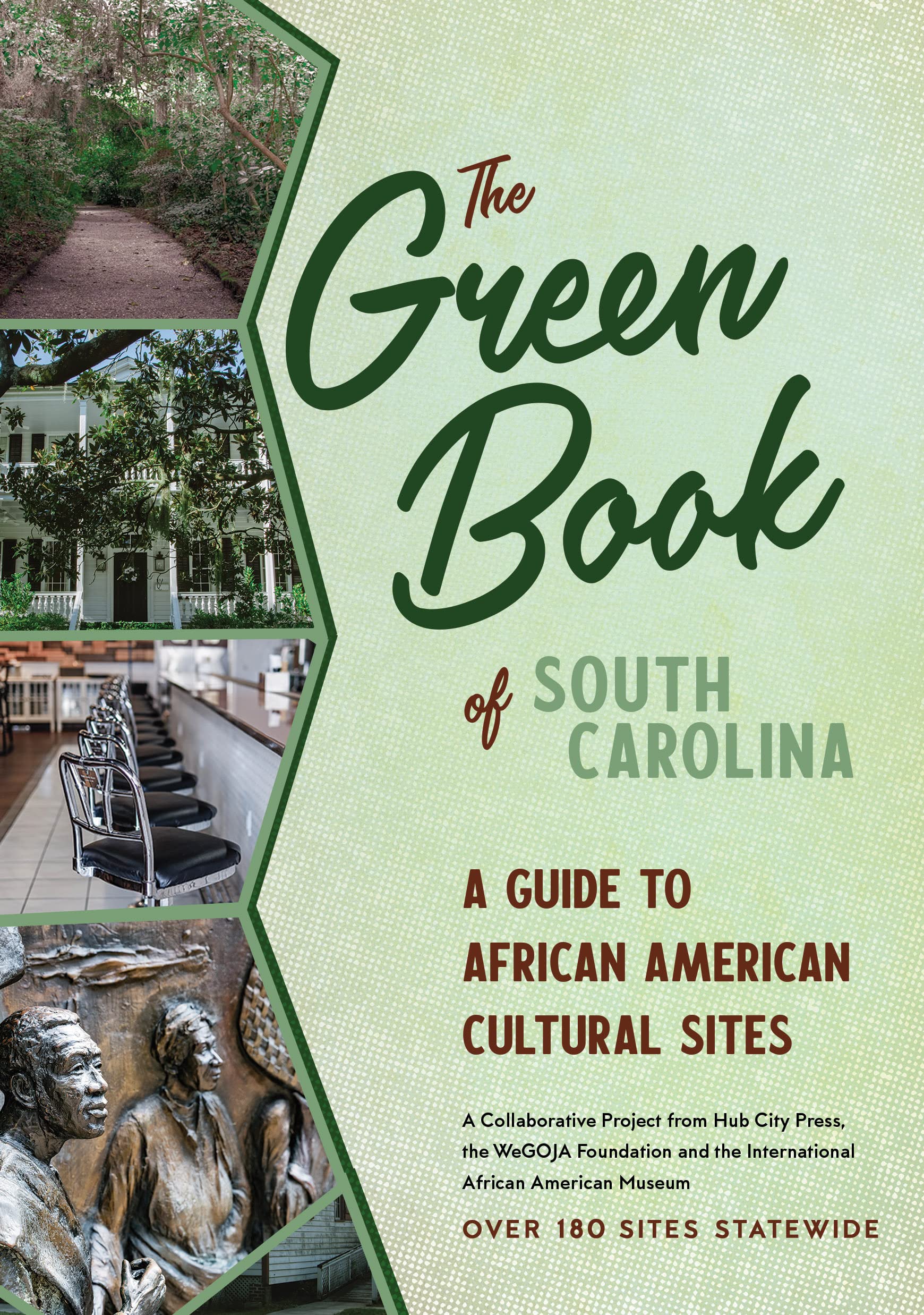

In a recent episode, Holly Jackson is "By The River" with author and photographer Joshua Parks discussing The Green Book of South Carolina: Travel Guide to African American Cultural Sites which has more than eighty of his photographs inside. Joshua shares the history he’s discovered through the people. Holly takes a look into the rich world of South Carolina’s site preservation and the stories they tell.

Tell us a little bit about yourself and how you became part of this project and what this project really is.

The majority of my family is actually from a small island. Legare Island is located right near the coast of James Island. And coming to Charleston, well, James Island, growing up, it was a lot slower. The pace was a lot slower, and it was a lot more rural. That change of pace always kind of intrigued me. I got into photography as a documentarian, just shooting photos of my family, and shooting photos of places that I've been. I really like to credit my uncles who subconsciously, and not even just my uncles, but a lot of the elders in my family who always had large photo books and photo collections. As a kid, I would always go through the photo collections of our family, and I always loved going through the photos. That’s what really brought me to this project. When I got hired at the International African American Museum, Dr. Brenda Tindal, who hired me and who I was working with, she told me about the Green Book Project. And this was actually the first project that I got put on when I got hired.

For those who don't know what the Green Book of South Carolina is, how would you describe it?

I would describe it as not only a travel book. Just for some background context, The Green Book of South Carolina is inspired by the Green Book, which Black travelers used during the Jim Crow era to travel throughout the South, the Midwest, and the North. So there was a Green Book by Victor Green that was published in 1936, all the way up until the 60s. This is inspired by that Green Book in the spirit of traveling in the spirit of Black cultural and heritage sites. This book is a little bit different because it highlights cultural sites that may not necessarily be functioning right now. Some are small houses and churches that are trying to be converted into museums and into cultural sites. It highlights the people as well who are doing the work, who are like stewards in those communities, and who are trying to get these historical sites up and running and functioning. A lot of them are sites that would've been featured in the original Green Book, but now they're not necessarily utilized the same way.

One thing that I'm always amazed by when it comes to a photographer, you have to pick that one image and you want that one image to tell such a big story. How difficult was that in this case, especially the ones that are not just a building? Whenever you're incorporating the people, what kind of challenge was it to pick that one photo?

That's the hardest part. I took a lot of photos. It was difficult to arrange for people to be in some of the locations because it was statewide and some of the folks had difficulty, some of them were elders. I really want to credit Dawn Dawson-House, who was with the WeGOJA Foundation, and was really the architect of putting this book together. She would basically put me in contact with the community stewards of those historic sites. Then we would meet up and they would usually take me on the tour and tell me about the site. I would get to explore the site and I would take a lot of photos, but I really made it a point that I didn't want the book just to be buildings or landscapes. I really wanted it to be people and faces. Meg had the privilege of choosing a lot of the photos because I couldn't do it. I fell in love with a lot of the photos and would've been very difficult for me to choose one or two to represent a certain site. I trusted Meg.

What was kind of your takeaway collectively from them that they want, what message do they want to get across to the generations who follow?

I think really what they [the elders] want to get across is that our history is important. That we have to be the stewards and the storytellers of our own history. That they have paved the way and that they've done their part right. A lot of 'em, they're tired and they really want the younger generations to step up and pass that baton. Now you have to be the one who makes sure that the taxes are paid for this building and that make sure the building isn't falling into disrepair or taken to the next level. Trying to inspire, it's your job to figure that out, and really the only way to preserve the history is to build these institutions and these organizations. So I think they've definitely led by example. If I could take away one thing from my journeys across the state is that it's time to pass the baton and it's time to get for my generation to really get serious about preserving this history.

Do you feel like you are a different person because of this project? And if so, in what ways?

Absolutely. I think that this project made me a better photographer and not even a photographer, in a technical sense, but a photographer as an ethologist or a photographer as an anthropologist, or a photographer as someone who not only takes pictures of pretty things and pretty people but takes photos that become historical records. I think this book serves as a historical record because a lot of these sites I would consider them endangered, and some of them in 20 years might not exist unfortunately. So I think that this project definitely gave me a deeper understanding of the role of the artists and the role of photographers when it comes to preserving history and culture.

What kind of stories have you heard from readers?

It’s funny, now that this book is out, we get more emails and calls about what we missed. It’s a good thing because now people are realizing that church down the street from 1889, that's not just an abandoned building. It’s history. It's worth being documented because I think this is a bottom-up version of history. Usually, we learn history from the top down, from the generals and the military men and the statesmen. This is a people's history. I think this really democratized what people feel is history and what's worthy of being recorded and put into a book. Once it's in a book now it's legitimate. I think that's good because version one almost necessitates version two. Now, people are like, oh yeah, I want my grandmother's church. which was already online. But, we wanted to make a print copy because we know people like actual books and, you might be able to carry around.

Who do you hope will be the readers of this book?

I hope particularly everyone. But I think this book is like a love letter to, Black Charlestonians, Black South Carolinians. To really, appreciate their history, and hopefully a younger generation can pick this book up and see that this history is worth telling and that we're still making history. You know, it's 2022 and we still have a lot of stuff to record. We still have a lot of things to do and we're still doing a lot of important things. Hopefully, this is an example of the importance of building organizations and institutions because almost every last one of these sites were once organizations and institutions that served the Black community.

What are some other ones that really stood out to you? Either people or locations that you'll just never forget?

Being my family's from the Lowcountry, so I'm very Lowcountry oriented, sure, but this book forced me to break out of that. I had to travel throughout the state. I had to travel all the way from the Lowcountry through the Midlands to, the Pee Dee region, all the way to the upstate Piedmont. I think one of the sites in the Upstate that really stood out was, it was in Seneca, the Berkly Bertha Lee Strickland Museum and Cultural Center. Essentially, this is a home that was converted into a museum and cultural center, which a lot of these sites are in a sense, but this really stood out because of a lady named Ms. Shelby Henderson, who is the executive director of that museum. I was going there to photograph the site and I showed up and I just started photographing outside, not thinking much of it. I see this woman walk out of the building, I didn't know anyone was in the building. And she's kind of like suspiciously looking at me like, what are you doing? I told her who I was and I told her what I was doing and she was already familiar with the project, very integral in this project. Ince she realized who I was and what I was doing, she just kind of welcomed me with open arms. And she took me to lunch and we just talked. She just told me all about the history of Seneca and the history of Black people in the Upstate in general. The stories that I heard and what she shared with me gave me a very deep appreciation for South Carolina history in general because the Lowcountry does get a lot of shine when it comes to telling the story of South Carolina. I think just being able to go to the Upstate and meet so many people from the Upstate gave me a broader perspective of and appreciation of Black history in Black people throughout the whole state of South Carolina.